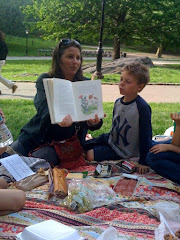

Over the past weeks, those of us Davises and Pearls who survive him have thought about him and about how we want to acknowledge this milestone. Today we drive to Boston to be with my mom, brother and his family. Eric, me, Gus, and Henry. We'll all eat together, we'll bring a guitar and try to get everyone singing, we'll do whatever my mom feels like. There's no gravestone. No cemetery. She doesn't want the kids to forget him. Little does she know--no one could ever forget him. How could they? She took his jar of ashes and put a Yankees cap on it.

Fall in Massachusetts is so beautiful. It will be impossible not to think about the raking of the leaves, the foliage on Moose Hill Parkway, the decades of my mom's great cooking, and all of our family dinners. If anything was happening in the world, my dad could explain it to us. He just seemed to know everything. Dinner time was when we'd get all our answers. I know how hard it is for my mom to sit through the presidential campaign without him by her side. He had such a uniquely expressive sense of moral outrage.

Going forward, I will write more about the times when he was alive, but for this one year anniversary, I guess I'll share the story of what happened to us that night one year ago. It would be lovely to spend the time remembering my 44 years with him before this day. At the same time, I acknowledge and accept that being with him in the moments I describe below was probably the luckiest thing to happen to both of us. The truth is that I feel honored that I was the one to be with him when he died. And though I miss him every minute, I appreciate that I will never have to see him get old and frail. Though it seems unlikely as I recount the events of that October night in Udaipur, I know watching him grow old would have been even harder. I see my friends going through the long slow torture, and I look up and say to my dad. "You sure did it in style, shnookums."

BE STRONG

October 19, 2011

“Ambulances don’t come here,” said

the voice at the front desk.

My dad lay listless in his bed. It

was awful. Around nine he’d gotten up to use the bathroom in our little hotel

room, but didn’t return. No sound came from the shower or the toilet, but the light

was on. I peaked around into the bathroom door, and there I saw him--laying on

the tile floor, ghostly and unconscious.

We’d arrived in Udaipur, “The

Venice of India” that day, tired ourselves out on a tuk-tuk tour, and jumped in

our hilarious side-by-side father/daughter beds knowing next to nothing about

our environs. It was good we shared a room, after all.

“Dad?” I had prodded him as he lay frozen

on his side. Hearing his name, he thawed a bit, and came to. He asked what

happened. We got him up and into bed--but he was out of it. He’d hit his head

and there was blood. I’ll admit I was really, really scared.

“I need help,” I told the front

desk. “My father’s sick. I need a

doctor!”

His next episode happened a few minutes

later--like fainting, but worse. “He’ll be fine,” assured a doctor an hour

later. “Would you stop asking me about oxygen!” He scolded me for my behavior as

he left the Haveli, but nothing could explain his behavior. He didn’t connect

or seem to want to.

Thinking back to this time just a

year ago—we were both getting ready for our fifteen-hour flight from Newark. We’d

had our shots, pills, etc. I wasn’t worried about malaria as much as jet-lag. My dad only worried about his lesson plans for

teaching. When I spotted him at Newark, he wore a smirk like Indiana Jones. His

sense of joy was palpable. Mine, I hadn’t yet realized, was compromised by a

sense of responsibility I hadn’t felt since I was a brand-new mom. My dad:

Beloved professor, staunch humanist, Doo-Wop aficionado, affectionate beyond

description, klutz. Me: the one who’d printed out twenty pages of “what-ifs”

from the state department knowing I was going to a place I’d only seen in

movies with words such as Slums in the title.

So we went, just he and I. My mom

stayed in Boston. India was too damn hot.

He’d teach secondary teachers at

the American School in Bombay; I’d meet with elementary kids and talk about my

writing. We’d have five days there, and then fly north to see beautiful Rajastan.

Yet here we were, on the first night of the second leg of our adventure, and something

had gone terribly wrong.

When the men with the stretcher finally

arrived, I breathed again—I’m not alone.

But my confidence crashed when I saw their so-called ambulance. Was I expecting

a hospital-in-a-van like in New York City? Maybe so, because this ambulance was

an empty van—no oxygen, no EMTs, not even a strap for the patient. Guess we’d

just have to rush to the ER.

My dad lay covered in the softest

white duvet from our room. I sat by his side, rubbing his arm as we drove, mostly

trying to keep the gurney (and him) from rattling up and down. A cow ambled across

the narrow road in front of us. It was

like Monty Python here. I looked down, wanting to tell him about the cow. But

instead he told me something: “If I wasn’t nauseous before,” he croaked, “I’m

nauseous now.” Any other time, I’d have laughed out loud at our absurd

situation, our crappy luck. But there was no laughing this time. I’d never felt

this alone, this responsible, or this afraid. The bottom was falling out—I felt

like a nursing mother who couldn’t produce enough milk—or someone who’d just seen

her child fade from sight across a busy intersection.

At the ER, a doctor leisurely measured

his oxygen level as others looked on. “Just

get him oxygen!” I was emphatic and panicked. Didn’t anyone get it? Anyone? Hello? Next I spotted something on his

face--something no one noticed. He looked frozen. His eyes had gone glassy.

“Look! Look!” I yelled, “Look!”

Now it was really happening. I was

ushered from his side—pushed outside a curtain. But I watched everything—my

body floating above, screaming. I was turning inside out. He wasn’t responding

at all. I answered my phone. It was my aunt. “My dad’s dying.”

“Go be with him,” she urged. She’d

been trying to reach me. “Touch him, tell him he’s not alone.”

I did those things, but he was gone.

Later everyone asked: “How did you

hold it together?” I didn’t. I cried without

stopping for the rest of the night. I looked at his suitcase, at his sandals,

and waited for something to change. On the phone I told my mom I was all right.

I heard my husband cry.

The real job of holding me together

came the next day, and it fell upon the men from Amet Haveli, the hotel. Horrified and concerned, some of them had followed

our ambulance the night before, and never left the hospital; another was sent

by the hotel owner to help me. Even the waiter from the hotel’s moonlit cafe had

stood next to me in the room where my father’s heart had stopped beating. He

came over to me in the aftermath, his eyes filled with tears.

The only woman I saw that night was

the ER doctor.

The rest were men. Everyone of them

used the same two words: “Be strong.”

So I tried.

We knew our dad wished to be

cremated, his ashes scattered in Coney Island, so my brother and mom both

agreed. We’d respect his wishes. The man sent to help, called Gchouan, offered

a traditional Hindu open-air cremation as a funeral. He brought me to see the

place. It was just a long slab of concrete with some pyres. The area behind it

strewn with garbage. A few filthy Hindu monuments. Nothing we’d ever see in the US. How long had

the place been there? Centuries?

The cremation took place only after

a long day of mind-numbing Indian bureaucracy. Another man, Reggie, helped me,

too—“our guy in Udaipur” as the gal at the consulate called him. We needed

Reggie to help convince the police that I didn’t want an autopsy at the

government hospital. Nearly a dozen men discussed the issue for three hours or

more. I didn’t care what it took, I didn’t want him cut open in a place that

wreaked of dog shit. Besides, after the ER experience at a private hospital, I didn't want to know what this place would be like. Instinct took over and I refused to lose him again. Let his body stay whole.

Finally extricated from the filthy

government hospital, his body, wrapped in muslin was slid inside the white

painted funeral vehicle’s long cubby. Reggie motioned for me to climb onto the

back, and we sat up top on a bench next to my dad as we made our way. Traditional

Indian Music played as picture of Ganesh smiled down at us. Remover of Obstacles.

As we drove through the streets, the

people of Udaipur heard the sounds of the Indian music. When they saw us, they stopped.

The white vehicle with red painted Indian writing, the music, everything signaled a tradition. I was the only

one who didn’t know about it. Staring into my eyes to make contact, the beautiful

people in their pink kurtas and orange cotton saris, placed their palms

together respectfully, and bowed to me and to my dad. Many, many others joined

in as we drove. A few gazed past my swollen eyes right into my breaking heart. Riding

behind us, like valiant soldiers on horses, were the men from the hotel on

their motorcycles. A few hours earlier, I’d wanted to bury myself alive—now,

somehow, I felt elated. I felt like a Kennedy child, maybe Caroline. I took

pictures as if I’d show them to my dad later. I spoke through my tears, “Dad,”

I said, holding onto the flowers that were placed there, “You wouldn’t believe

how beautiful this is.”

We arrived as workers sorted wood

for stacking on the pyre along the concrete platform. Soon, we carried his body,

our poor sweet bundle, to the place it would never leave.

Now he lay cradled on the wood

branches. Gchouan was my guide. He told me that soon they would unwrap my

father, exposing his face and chest. “Be strong,” I remembered. So I braced

myself. From five or six feet back I watched, my eyes half closed just in case

I saw something I couldn’t bear. But as the gauzy white was ripped and pulled

open, I saw him again. Dad. He looked pink and beautiful. His nose was mushed,

but not terribly.

A man opened a box of ghee

(liquefied fat, like butter) and then another—pouring both on his body. After

flowers had been placed around his neck, I was handed a cluster of twenty or so

tiny smoking twigs. “You hold them near him and it symbolizes that you lit the

pyre.” They told me that women were only allowed here if they were the dead

person’s only relative. They poured water in his mouth after placing a coin inside.

That part was bad. Too uncomfortable for him. I didn’t want a coin in my mouth,

why would he? Now was my time to touch him. I reached out my fingers and felt

his soft gray hair. Maybe this was my way of saying good-bye. As I write, I can’t

remember the last time I kissed him.

The pyre was lit, and in some spiritual

way, I suppose I was glad for him. Glad he wasn’t cut open at the smelly

hospital. Glad he didn’t suffer too much. Glad that even though the country of

India had the worst ambulance ever, they knew how to do this part right. Gathering for a group picture, the dozen men and

me, it felt like we’d fought in a war together. My brother was with me, too, thanks

to the miracle of modern technology, and I was grateful. He said he’d tell our

mom what was happening. I couldn’t bear to think about her pain.

“It was predestined,” these saddened,

kind, locals told me afterward, grasping my arm in the place I’d held onto my

dad’s the night before. I wish I believed it—I really wanted to. Though I can

tell you one thing, my dad wouldn’t have bought that line in a million years.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)